Picture this: there is a classroom of 30 students, all attending the same lecture and solving the same questions, but still, there is a wide gap – a gap in cognitive abilities. Some students are skimming through the questions as if its nothing more than a trivial mental exercise, while the others are stuck, concentrating, reading the same text again and again, trying to figure out what and how of subjects.

This is the story of every classroom, a story that parents and teachers are well aware of. But have you ever wondered why there is this gap in learning institutions, why some students excel while others struggle, even when learning from the same teacher, the same textbooks? If you answered yes, this article is for you!

In this post, we will uncover the hidden factors behind academic success. So stay tuned to understand the real reasons behind it.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

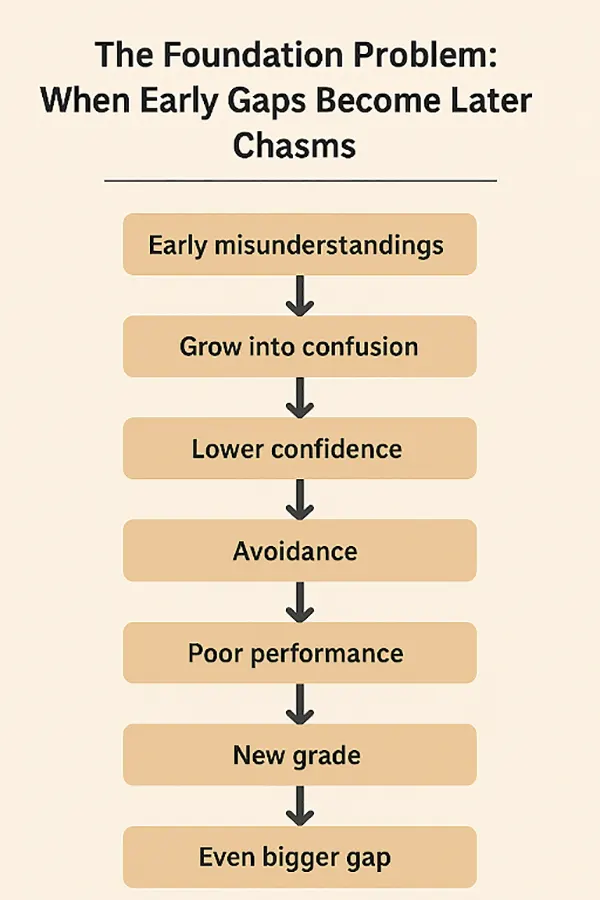

- Gaps in the foundation can later become chasms.

- Even gifted kids sometimes struggle due to metacognition gaps.

- Ignoring executive function skills is one of the biggest faults in the education system.

- Some students focus on real-world preparedness rather than on theory taught in classrooms.

- Parents play a crucial role in a child’s academic performance.

The Foundation Problem: When Early Gaps Become Later Chasms

“Strong foundations make hard lessons lighter.”

The problem doesn’t start with the seemingly hard lessons; it starts way before that. Small learning gaps in studies can turn into bigger holes tomorrow, and this is exactly where students struggle.

Let’s understand this with an example, suppose a child never fully grasped the science concepts in primary 3, he/she will definitely find these concepts harder when these topics appear again in p4. To support such students p4 science tuition plays a crucial role. It will help rebuild and revise the concepts that the child might have missed in the previous lessons, reforming its foundation for better performance in the future.

The infographic below shows how early gaps can later become chasms.

The Metacognition Gap: Why “Smart” Kids Sometimes Struggle

You might have observed that even the gifted students sometimes struggle, but why? Well, the reason is the metacognition gap, or in simple words, they never learned how to learn. Metacognition is the ability to understand one’s own thinking. It might sound simple but it plays an important role in a student’s academic success.

Students who lack these skills often study without strategy, misjudge their level of understanding, overestimate how prepared they are or repeat ineffective study habits. As a result, they underperform even after having the potential and capability to do better.

So, what’s the solution here? The student must ask themselves questions like “what do I already know?” or “how can I break this into smaller parts to learn better?” This way, they can focus more on clarity instead of capacity, improving themselves.

FUN FACT

Your brain literally gives you a ‘reward’ for understanding something. This reward is “dopamine”, the same chemical that is released when you eat chocolate or win a game.

The Hidden Curriculum: Executive Function Skills That Schools Assume You Have

The majority of the schools only focus on teaching subjects and ignore important executive function skills, a major fault in the education system!

Executive function skills include organizing materials, managing time, planning ahead, prioritizing tasks, controlling impulses, and staying focused despite distractions and this set of skill is extremely important for students and makes a real difference between high achievers and struggling students.

The Career Preparedness Paradox: Learning Skills That Matter Beyond the Classroom

Rote learning methods and focusing on only theory don’t excite many students, and this can be one of the reasons why they might underperform. However, when learning is linked to real-world relevance, it triggers their curiosity and motivates students to learn more.

One such future-ready, practical course is food safety course at coursemology, which helps students understand how the things they learn in the classroom apply beyond those four walls.

The Parent Factor: When Involvement Helps Versus When It Hinders

Parents can be a big factor in their child’s academic performance. Yes, they can be a positive factor but more often than not, some parents unintentionally turn into quite the opposite and do more harm than good. Here’s how parents’ involvement can affect their children:

| Helpful Involvement | Harmful Involvement |

| Encouraging routines | Over-controlling study schedules |

| Providing a quiet study space | Comparing children to others |

| Supporting mental and emotional well-being | Setting unrealistic expectations |

| Understanding the child’s pace | Doing the child’s work for them |

The right involvement from the parents’ side can boost a student’s confidence, while the wrong one can induce anxiety and burnout.

Beyond Grades: Defining Success More Broadly

Grades are not the defining factor for any child. There could be many underlying reasons why a student might be struggling in academics, but it does not mean that he/she has a low IQ or is not intelligent enough.

Some other factors, like creativity, leadership, communication, empathy, and problem solving are equally important for future success.

In the end, parents and teachers must know that their role is to encourage students to develop their strengths and not just chase perfect grades. Also, supporting students not only means helping them grow academically but turn into confident, capable people who are ready to take all the challenges life throws at them, with a smiling face.

Ans: The factors affecting students’ academic success include study hours, previous scores, gaps in the foundation, mental pressure from external sources, etc.

Ans: Yes, foundational learning gaps can affect a student’s performance years later.

Ans: Absolutely, parents play a crucial role in their child’s academic success. Their support can help boost confidence and on the other hand some actions might even have a harmful impact.

Ans: Yes, stress and anxiety are two factors that directly interfere with working memory, focus and problem solving.

![]()